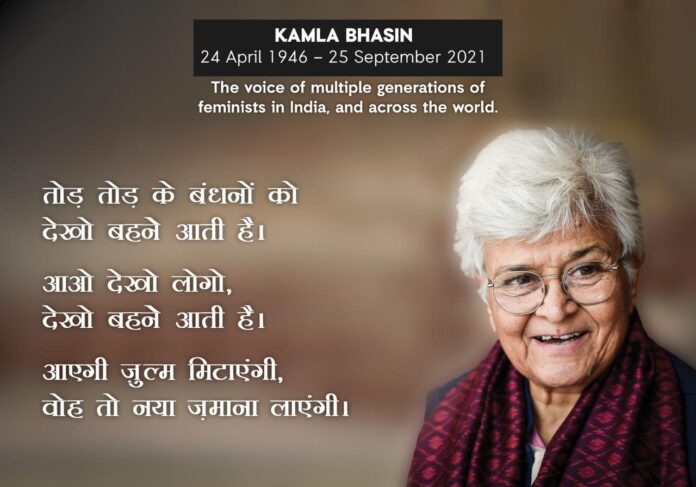

(By Dipali Sharma): Kamlaji’s death sent me down memory lane. I relived my life journey as a young small-town girl to a newlywed woman in the national capital and the woman I am today.

Growing up as a young girl in Gwalior, the one thing that I dreaded most was rape. Hindi cinema has impacted me a lot. In the movies I watched in the 1980s and the 1990s, the raped girl would invariably commit suicide. The girl lost her honour, as well as the honour of her family. The danger of a sexual assault was not unreal for me. Though my family was exceptionally caring, the adolescent me thought that killing myself would be the only way if I ever became a victim.

Gwalior was not safe for girls and women. Walking on public roads, using public transport, even if it was to go to school, then later to college, led to getting my share of harassment, including cat-calling or “eve-teasing”, and groping. I was fortunate that I never experienced anything worse.

In the mid-nineteen nineties, I moved to Delhi to work with ActionAid, which had the reputation of being an ‘international organisation’. I was newlywed, in my mid-twenties, and I wore all the symbols of a married woman, from head to toe.

At the office, I found that I stood out because of all the accoutrements of a married woman that I would wear. My work at ActionAid India, and since 2006 ActionAid Association, started a battle of ideas in my head. There was a struggle between society’s expectations of me as a married woman and my changing awareness of my identity as a woman and as somebody working for social change.

(Director – Organisational Effectiveness, ActionAid Association)

Kamlaji played a significant role in the transformations I experienced in my life. Kamlaji was regularly requested to conduct training programmes with colleagues at ActionAid to further our understanding of gender and patriarchy. Kamlaji used straightforward language, drawing on practical everyday life examples. Her approach was learning through fun without losing the seriousness of the issues under discussion. A question often asked in several of Kamlaji’s training sessions was: “It is women only who are the enemy of women. It is the saas and bahu who fight with each other. It is women only who ask for dowry and result in many divorces.”Kamlaji would take up such questions in detail. She would help explain, “The saas who herself has gone through oppression and subjugation as a bahu, suddenly derives ‘the patriarchal power’ after becoming saas, being the mother of a son and exercises that power denied as a bahu.”

Kamlaji would explain how feminism is a fight against the ideology of patriarchy, the ideology of the supremacy of men over women and not a fight of women with men or women with women. She showed how there were women who would behave in patriarchal ways. She would help us understand the social construct of femininity and masculinity before slowly get into the realm of the relationship between patriarchy, the neo-liberal economic paradigm, the capitalist plunder of Planet Earth, the fundamentalist and fascist tendencies tightening their grip over the world today.

Kamlaji dedicated her whole life to these causes. She did whatever she could till the end of her life, engaging herself in teaching and training people on these issues. She wrote hundreds of books, songs, slogans that will continue to inspire many, many generations. She lived by her ideals till her last, and her mortal remains were, as per her wish, consigned to the electric crematorium to save wood.

Kamlaji was the epitome of love, peace, simplicity and positivity. She was a crusader for peace in the South region. Even during the last few hours of her life, while battling liver cancer, she attended a virtual meeting of the Pakistan-India People’s Forum for Peace and Democracy. Such was her strength, dedication and resolve. It’s been such an inspiration to read tributes from young feminists from many South Asian countries who attended Kamlaji’s South Asia level feminist development programme.

As a young bride, I was expected to observe ‘karvachauth’ every year. On this day, married Hindu women, mainlyfrom North India, would observe a fast from sunrise to moonrise for the safety and longevity of their husbands. Working in ActionAid and after the experience of Kamlaji’s training sessions, I decided to stop keeping that fast one day. Kamlaji’s words rang in my head. “All husbands in America should die early because their wives don’t observe karvachauth. Why is it that only women must fast for their husbands, their sons and worship their brother? If it is for love, then husband and wife, mother and son, brother and sister both should do it together out of love and respect for each other.”It was difficult for me to change this practice of generations in the family. Family and friends constantly asked why I was not observing fast, and I felt the psychological pressure of being seen as someone who didn’t care about her ‘husband’. My partner’s support and eventual acceptance of my decision in the wider family and friend circle have built my conviction,and I realised that change is possible though it may be a slow and gradual process.

Today, we do puja (not karvachauth), but we have amended several gender insensitive lines in the hymns and prayers recited during puja.

I have managed not to project my adolescent fears of sexual violence to my daughter, and again credit for that goes to Kamlaji. She stated it bluntly, and many times, “A woman’s honour or, for that matter, her family’s honour is not in her vagina. When a woman is raped, it is the man who rapes who loses his honour. Only a man whose humanity has died within him can commit such a heinous act.” I have tried to raise my son such that he keeps his humanity and his honour intact.

We celebrate Kamlaji’s life and contributions and resolve to carry forward her legacy. I share my memories as my humble tribute to her and her work.

(Views expressed in this article are personal and do not necessarily reflect those of ActionAid Association.)